Ron Howard finds a story of survival in “The Beatles: Eight Days A Week”

Realscreen Magazine

While Ron Howard was making a documentary about the five-year period the Beatles spent touring the world, the director drew an unlikely parallel to another one of his films. Apollo 13, the 1995 feature about NASA’s disastrous moon mission, is a story of survival. So was Beatlemania.

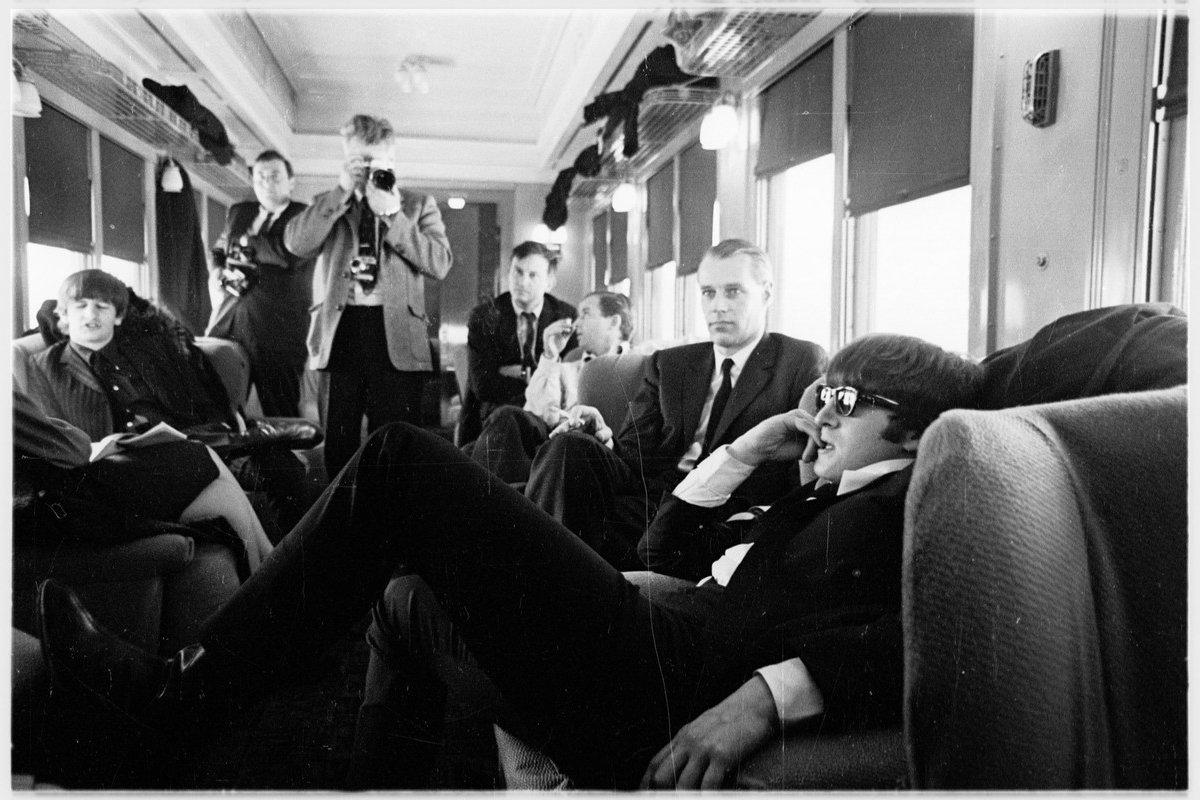

In the documentary The Beatles: Eight Days A Week – The Touring Years, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr hit the road in 1963 fresh faced and ready to experience the world.

By their final show in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in 1966, they were intensely famous, disenchanted with the media and unable to hear their own music over screaming fans. Despite making the majority of their money from playing live, they retired from touring to focus on making music in the studio.

“In Apollo 13, you have three guys in a capsule trying to figure out how to survive a crisis and not die,” explains producer Nigel Sinclair, who also produced Martin Scorsese’s George Harrison doc Living In The Material World. “That’s an extreme thing, but it’s three people thrown into a situation and making decisions together. Although you can’t parallel the Beatles journey, you could list half a dozen examples of young people that faced the onslaught of public life and fame but disappeared into drugs or chaos.”

Produced by The Beatles’ Apple Corps with Sinclair’s White Horse Pictures, Howard and Brian Grazer’s Imagine Entertainment and coproduced by One Voice One World (OVOW), Eight Days A Week is the first official Beatles film since the 2003 TV doc series The Beatles Anthology and the first official feature since 1970′s Let It Be.

The challenge for any filmmaker interested in working with the Beatles and Apple Corps is one producers had to overcome in presentations to surviving band members McCartney and Starr, as well as Lennon and Harrison’s widows, Yoko Ono and Olivia Harrison. That is, what else is there to say about the group that hasn’t already been said over the past 50 years?

Howard and Sinclair wanted to satisfy discerning, long-time fans of the band, but they also wanted Eight Days A Week to appeal to younger audiences.

“What millennials are interested in, I am told, is the why of things – not the what,” explains Sinclair. “Why did the Beatles become so perfect? How did it go so powerfully for so long? What was the magic that made it work?”

The idea for the film began in 2003, when producer and archivist Matthew White pitched a project about the Beatles’ touring years to Apple Corps. Then a producer for National Geographic, White thought of the idea after coming across archival footage shot by Nat Geo wildlife filmmakers in Alaska when the group’s plane was diverted to Anchorage en route to Japan in 1966.

“It made me realize that wherever the Beatles went there were cameras,” says White, who founded OVOW with producer Stuart Samuels and Bruce Higham, cofounder of ’60s London club Sibylla’s.

Realizing the rise of Beatlemania coincided with the widespread availability of 8mm home movie cameras, he initially pitched the project to Apple Corps as a doc that would tell the story of the group’s live tours through amateur footage.

White was also interested in doing a project that would be led by archive. Rather than come up with a treatment first, the idea was to amass archival material and let it shape the story.

Moreover, he hoped an archival-led Beatles doc would demonstrate the value of preserving deteriorating footage as part of programming budgets.

“Most filmmakers go into archives trying to look for material that supports the story, which is not the best use of archives,” he says. “There are things in there that [you] might miss or might not be what you’re looking for.”

After leaving National Geographic, White began researching a proof-of-concept to see if he could find footage that Apple Corps had not been able to uncover for the Anthology. He approached specialty 8mm transfer houses and asked if anyone had brought in Beatles films.

Massachusetts-based Brodsky & Treadway connected him to a collector named Erik Taros, whose mother refused to let him go to the Beatles’ 1966 show at Suffolk Downs near Boston.

He’s spent much of his life collecting home movies, photos and fan memories to recreate that concert. Taros would prove a pivotal contact.

“He’s part of an underground collectors’ network that exists in all of the places the Beatles played around the world,” explains White. “They work with each other but aren’t public about what they do.”

Members of the secretive network were scared to give their material to the Anthology for fear it would be taken away. Moreover, they often buy Beatles footage and audio at auction houses such as Sotheby’s and exposure via films can lessen the material’s resale value.

Meanwhile, Jeff Jones became the CEO of Apple Corps and was interested in finding ways to exploit unseen archives the band controlled. He had been keeping track of OVOW’s project and in 2012 financed a six-month archival search based in the University of Maryland with 30 researchers around the world.

The search yielded the only known footage of the Beatles performing in Madrid, British Pathé’s 35 mm color fi lm of the 1963 London Palladium show, clips of the band performing on a Scottish kids’ show in 1964 and good quality soundboard recordings from a number of concerts. White and Taros then flew to London to review what they’d found with Apple Corps.

“By the end of it everybody was just high from all the different things that we were finding,” he says.

Apple Corps greenlit the fi lm and brought White Horse and Ron Howard on board to make it. A year later, in May 2014, they went public and asked fans to submit amateur footage via a website advertised on the Beatles’ Facebook page, which has more than 40 million likes.

Fans discovered the White Horse office number and jammed the switchboard for three days. In all, producers amassed 2,000 separate pieces of audio and photographic images that needed to be cleared and cleaned up for the screen.

The final film mixes amateur footage with archives from the Beatles’ collection and archival sources. It began rolling out theatrically on September 16, with Abramorama handling U.S. distribution, and became available on SVOD platform Hulu a day later. It is the first film acquired by Hulu Documentary Films, which launched in May.

With 100 minutes to tell the story, Howard focused on big themes such as the group’s tight-knit relationship, how it unfolded and how the band stopped touring to protect that relationship and their ability to make music together.

The closeness of that relationship was evident in both the footage and in decisions they made. In 1964, the band went up against segregation in the American South by refusing to perform at the Gator Bowl in Jacksonville, Florida unless black fans could freely mix with white fans – a moment recounted in the doc by Kitty Oliver, one of a few black teens who attended the gig.

“They were like an arts collective,” says Sinclair. “English men don’t really like to touch each other. We’re shy in public. With the Beatles, this sense of this chemistry between them really comes across in photographs. They’re so good at presenting themselves as a foursome.”